How ideas about nature shape processes of tribal identity: Two sides of tribal ecologies in contemporary India

This blog post emerges from a 2022 workshop, hosted at the University of Copenhagen’s Centre for Applied Ecological Thinking (CApE), which brought together academics and NGOs with varied backgrounds.

By Stephen Christopher, Matthew Shutzer and Raile Rocky Ziipao

Over three days, we discussed what we will here begin to call ‘tribal ecologies’ in contemporary India. We hope that this concept is analytically useful to scholars working at the intersection of tribal studies and ecology, sustainability studies, political ecology and anthropology.In a short space, we bring theoretical specificity to tribal ecologies and consider its applicability at different scales of analysis—from the local ethnographic encounters of tribal communities with the Indian state to the transnational mobilization of indigenous rights through international institutions. The goal is to carve out an emergent field of study that is equally applicable to academics and NGO practitioners working among tribal communities.

In India, there are 705 ethnic groups recognized as Scheduled Tribes (ST), a federal criteria for determining tribal status inherited from the census practices of the colonial state. As we detail below, we use the term “tribal” to invoke this complex relationship between group identity and state recognition. While “tribal” can have many negative connotations, frequently relating back to colonial stereotypes of primitiveness, in contemporary India it is also a state-designated site of social aspiration and a moniker used by members of Scheduled Tribes to refer to themselves. The term Adivasi, meaning original inhabitant, is in some contexts a more empowering term used in substitution of “tribal”. In other contexts, however, Adivasi identities are rooted in provincial histories, primarily used to denote Scheduled Tribe communities from central and eastern India. The relevant comparative term in this case would be “Indigenous,” which today is used by many Scheduled Tribe communities to claim an historical connection with first nations and other Indigenous communities across the world. The Indian state, however, refuses to recognize the concept of “Indigenous Peoples,” and so it remains a deeply politicized naming practice. These overlapping but distinct naming practices are sometimes in discursive tension even within a single tribal community, where there is disagreement among competing interests.

Of course, there are many freighted intellectual antecedents for a discrete analysis of tribal ecologies in India. Studies of “traditional ecological knowledge” and “Indigenous sustainability” have long been part of global scholarly discussions of Indigenous peoples, particularly with reference to frameworks of Indigeneity that emerged alongside fields like evolutionary biology (Krech 1999). Ideas connecting Indigenous identities to nature took root during the colonial conquests of the early modern period, as comparative notions of property, legal personhood, and ethnological differentiation were constructed by measuring humans’ proximity to nature (Pagden 1987). These encounters produced the ideology of Indigenous “primitiveness,” a framework denoting social dependence on a nature insufficiently tamed by human intervention.

Tribes: Colonial constructions and contemporary identities

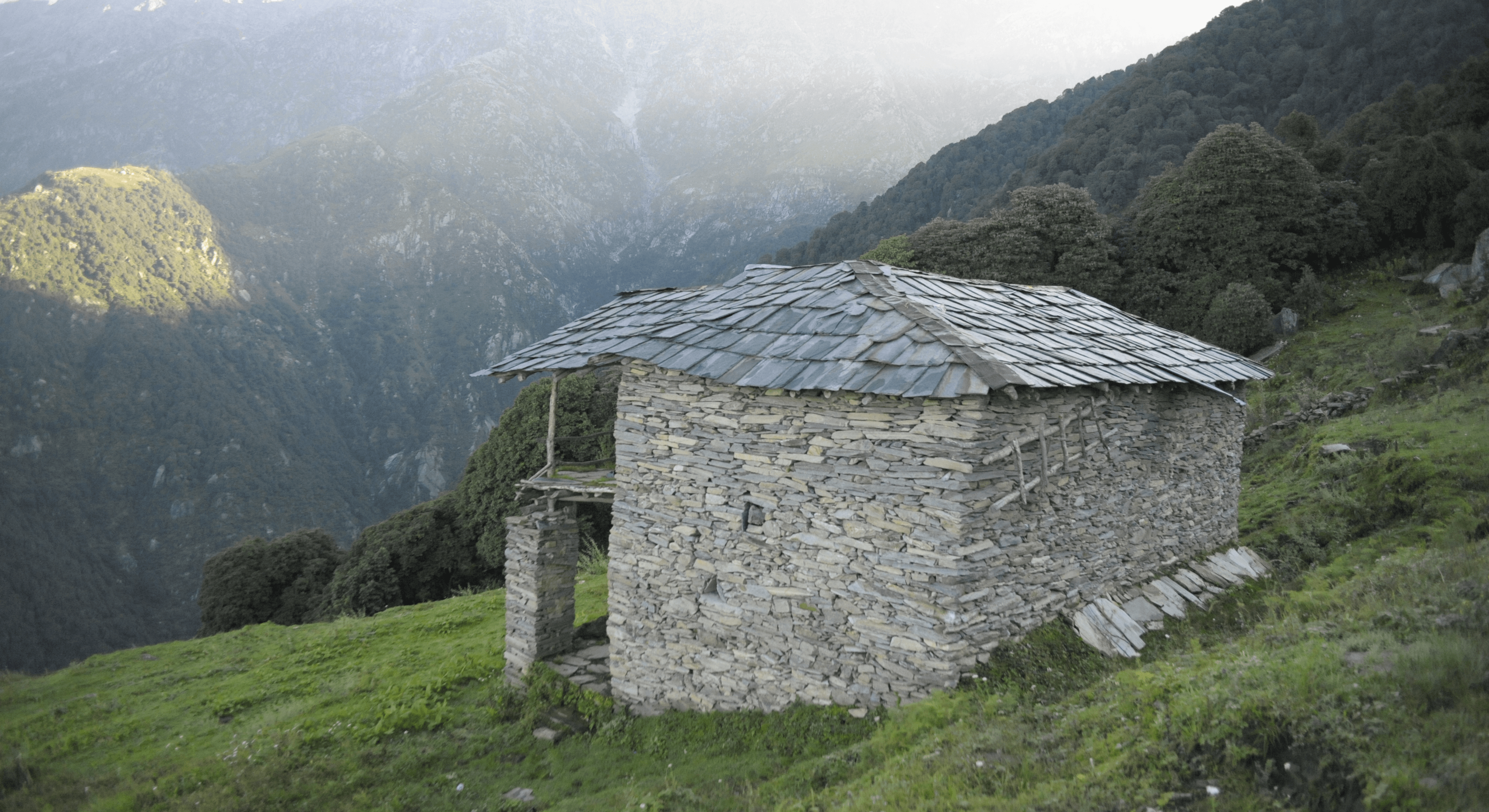

Beginning with European colonization in the sixteenth century, tribes were imagined as primordial, unchanging, and the lowest rung of social evolution (Bauman and Briggs 2003). Enlightenment projects naturalized the binary of European progress and tribal savagery, and anthropologists used evolutionist paradigms to divide up the social world based on stages of social development, from pre-state egalitarian tribes living in states of nature to state formations with complex social hierarchy (Morgan 1877). Such views privileged Western societies as both the apex of civilization and drew a contrast between modern alienation from nature and tribal synchronicity with nature. In many cases, such as in the Indian Himalayas, British colonial administrators deployed orientalist empiricism to ethnographically construct tribal society (Ludden 1993). Tribes practice pastoralism, transhumance, nomadism or foraging lifestyles; believe in animist cosmologies; are egalitarian; and use vernacular architecture and primitive material technologies not far removed from their natural state (Guha 1999). Some of these ‘tribal’ associations have shifted away from practiced lifeways to discursive tropes, as in the case of declining pastoralism among Gaddi youth (Christopher and Phillimore 2023).

As evident in the moving goalposts of tribal identity in successive Indian census reports, the ideology of Indigenous “primitiveness” did significant epistemic violence when put into practice. However, the postcolonial Indian state doubled down on such classifications in establishing the criteria for Scheduled Tribe recognition. During the Constituent Assembly Debates (1946-49), which culminated with ratifying the Constitution, assembly members debated the features of tribal inclusion and whether tribes should be protected as primitive cultural groups living in untamed nature or assimilated into mainstream Hindu caste society. Both sides of the debate won: the Fifth/Sixth Schedules ensured tribal-autonomous territories that roughly correspond with tribal homelands and the administrative category of Scheduled Tribe (ST) nudged tribal people towards national integration in all-India schemes of positive discrimination. In both cases, however, the ideology of tribal primitiveness living in symbiotic reliance on wild nature persisted. This is evident in the subjective criteria of the Lokur Committee (1965), which frames tribes as possessing distinctly backwards cultural features and residing in geographically remote and untamed tracts of nature.

Modern anthropology, founded as a colonial discipline, complicated some of the negative associations of ecological primitiveness by pointing to functional aspects of Indigenous stewardship over nature, even as these studies retained an idea of Indigeneity as the “wild” temporal other of modernity (Skaria 1997; Fabian 1983). This also manifests in the work of Indian state ethnologists who adjudicate the over 2,000 extant petitions by ethnic groups for formal inclusion in the Scheduled Tribe quota. These tribal petitions can go on for decades (Mayaram 2014), instigate intra-group communalism (Kapila 2008) and foment sub-nationalist agitations (Middleton 2016). Importantly, such petitions are intimately tied to grassroots ethnopolitical movements that mobilize ideas of tribal ecology and stewardship over traditional lands. To make sense of all this, a small team of government anthropologists tour India’s tribal-petitioning communities and decide their constitutional status based on a few hours of fieldwork and the essentialist framework of Indigenous primitiveness.

Parallel to these administrative processes, scientists and humanists alike have begun to invoke “Indigenous knowledge” as a way of talking about the limits of modern science (Kimmerer 2013; Gomez-Bera 2017). Faced with the widening ecological crisis of anthropogenic climate change, Indigeneity now reappears as a sign of positive alterity, a way of imagining sustainable ecological relationships outside of capitalism. Such accounts have opened the way for connecting Indigenous traditions across various ethnographic contexts to a wider strand of “subaltern” epistemologies for rethinking the future of ecological thought (Duara 2014).

Accordingly, there are “critical subalternist ecological critiques” of colonial constructions of water as a contested commodity in Latin America, (Betancor, 2022) as well as “subaltern ecologies” reflected in the practices of jugāṛa (resourceful, rule-bending workarounds) in the context of class precarity in India (Rai 2019). Among the Amazonian Yanomami, Ferguson (1998: 287-88) contrasts the systemic environmental transformations of modern states (including European expansions, epidemic-caused genocides and intensifying extractive practices) with the often more gradual and limited impact of “tribal ecologies” on the environment. When tribal ecologies rapidly change, it is often due to devastating “contact with previously isolated biotic communities” (Ferguson 1998: 88).

While the above-mentioned notions of tribal and subaltern ecology lack rigorous elaboration, Sarkar (2008: 6-7) reclassified several scholarly approaches as “subaltern ecology” and helpfully abstracted general principles. He draws an important distinction from the project of Subaltern Studies and takes to task some Eurocentric views of environmentalism for dismissing the “rich analytic traditions of subaltern ecologies which have been used to interpret and refine these Southern movements” (Sarkar 2008: 20). The general principles of “subaltern ecology” include to:

(i) recognize the interpenetration of socio-political and non-human environmental factors in determining the state of habitats and livelihoods; (ii) draw on both (non-human) ecological and social determinants to produce salient facts; (iii) endorse heterogeneity and contextual delimitation in the choice of analytic techniques from the ecological and social sciences; (iv) view struggles over “nature” as reflecting struggles between human interests in society at large; (v) agree with ecofeminists that women play a distinctive role in most social organizations, and therefore, in struggles around them; (vi) explicitly contest the asymmetry of power relations in those struggles; and (vii) include equity, justice, and ecological sustainability and enrichment as goals of the these struggles.

As Sarkar himself explains, applying such a rubric is fraught. Classic examples of subaltern ecological movements, like the 1973 Chipko movement in Garhwal, do not necessarily demonstrate proto-environmentalism, symbiotic tribal relationships to nature, or women’s unique propinquity with nature, as was argued by some at the time (Govindrajan 2018: 184). Such protest movements may reflect less of an anti-development agenda and more of a desire for Indigenous control over development projects and extracted resources. Likewise, Gaddi oral narratives about the state monopolizing grazing grounds and commissioning large-scale hydroelectric projects may reflect less of a subaltern ecology and more of a communal anxiety about the appropriation of tribal lands, resource extraction and rapid social change (Sharma 2023).

The crucial point is that tribal ecologies are not post-material but rather intensely concerned with safeguarding traditional proprietorship over natural resources, often through the demands of state recognition. This point contradicts earlier theorizing of environmentalism as primarily a “postmaterialist” concern of the Global North (see Nordhaus and Shellenberger 2007). Scholars of Indian tribes are well aware of the lower socioeconomic status of Scheduled Tribes vis-a-vis general castes and how their heightened precarity infuses tribal ecologies with an urgent materialism (for a lengthy discussion of ST physical and economic deprivations, see Das et al. 2012). We share Sarkar’s concern that theories of environmentalism that privilege post-materialist conceptions of individual expression, group belonging, and abstractions of the good life (which since the early 1980s have been associated with the Global North) do not track the material needs of Indian tribal ecologies. This is evident in both our scholarly approach and in the applied techniques of NGOs that draw on the concept of tribal ecologies.

What are tribal ecologies

To situate “tribal ecologies” within this genealogy is not a straightforward task. To begin with, the modern category of “Indigeneity” largely draws from the historical experiences of native peoples in the Atlantic and Pacific worlds, specifically referencing processes of settler colonialism and native genocide (Karlsson 2003). South Asian histories fit uneasily within this lens of analysis (Guha 1999). The very terminology used to discuss Indigenous peoples in South Asia is suggestive of this ambiguity. Adivasi, for instance, is a term that entered circulation in the early twentieth century to express the struggle for dignity and self-determination of Indigenous groups, emerging contemporaneously with Dalit struggles for similar aims (Omvedt 1988). Although its meaning of “original inhabitant” invokes comparative styles of Indigenous claim-making as “first nations,” “Adivasi” has become primarily associated with the specific regional histories of communities in the central and eastern highlands of the Indian subcontinent, rather an overarching descriptive terminology. Moreover, many Indigenous groups, especially in India’s northeast, do not use the term to self-identify (Xaxa and Devy 2021; Moodie 2015). In another ethnographic context, for example, the Gaddis of Himachal Pradesh in the Western Himalayas have long-standing social contestation over Dalit belonging within the Scheduled Tribe quota for Gaddis; while Gaddi Rajputs and Brahmins have appropriated histories of fleeing Muslim persecution and taking refuge in the Himalayas. There is evidence that nominally non-tribal Gaddis who are designated Scheduled Caste status deploy oral histories of indigeneity and sometimes self-identify as Adivasi (Christopher 2022). This presents a fundamental question about the operation of caste-based differentiation within Scheduled Tribe communities.

Another factor is the variable social connotations of the term “tribal” across India. Undoubtedly, the colonial inheritance of the term is generally derogatory and reflects ideas of tribality across the pre- and post-Independent Indian collective imagination (Bora 2010). In some ethnographic contexts, tribal communities have sought to disidentify with the “tribal” moniker (such as replacing tribal markers of dialect and animist ritual with standard Hindi and Hinduism). For example, Kangra Gaddis, especially in cosmopolitan Dharamsala (Christopher 2020) between the 1950s-1980s, expressed a degree of communal shame about their tribal dialect and public sheep sacrifices as they further integrated into Punjabi cultural life and the caste Hinduism of the plains people. Some Gaddis completed caste emendation forms and legally changed their caste (and subsequent legal status) from Gaddi Rajput to Rajput, dropping ‘Gaddi’ as a strategy of regional integration and local prestige jockeying. This led one Gaddi ethnic entrepreneur to create the Kailash Association, which boasts thousands of members, to rehabilitate Gaddi pride in tribal identity. From another perspective, however, Scheduled Caste Gaddis are currently petitioning the state for inclusion in the Scheduled Tribe quota, citing systemic tribal casteism and state misrecognition (Christopher 2020a). While some high-caste Gaddis were (and are) disidentifying with the identity of tribal, low-caste Gaddis have grassroots mobilizations to shed the stigmatizing idioms of Scheduled Caste (Still 2003) and be recognized as tribal.

This variability is within a single tribal community. Considering the tremendous diversity of tribal communities, and those communities currently petitioning for Scheduled Tribe inclusion, a spectrum of connotations about the meaning of “tribe” is evident - from liberative to stigmatizing, in some cases a rallying point of communal aspiration and in other cases an overdetermined pejorative or necessary evil. Despite this variability, the term “tribe” is widely used by Indigenous groups to suggest a shared history of ethnic, caste, and spatial marginalization, as well as state surveillance and criminalization (Singha 1998; Pandian 2009). Its ubiquity surely stems from the fact that Scheduled Tribe is foremost an administrative category, and that the capacity of groups to access state structures of public benefits depends on their classification as constitutionally protected “Scheduled Tribes” (Shah 2013).

These contextual and historically contingent processes, not only among Gaddis but evident in many tribal formations across India, call into question the straightforward definition of tribes as non-caste societies (and tribal ecologies as unmoored from caste politics). This view, foundational to the work of the Tribal Intellectual Collective, may make sense in some ethnographic contexts, such as the dichotomy of non-casted tribal hill peoples and casted valley peoples in Manipur and more generally in the Northeast (Ziipao 2021: 39); and may make less sense in other contexts, considering the Rajputization of tribes, partially-integrated Dalits in the margins of tribal life, and the two-sided coin of tribal casteism and tribal multiculturalism. We argue that tribal ecology is one vantage to analyze how group composition unfolds at multiple scales of analysis--within tribes, at their sometimes-porous ethnic borders, and in relationship to the State.

Our invocation of “tribal ecology” is not an effort to simplify or reduce these complexities of tribal identity. Rather, we see this terminology as enabling a deeper understanding of the specific ways that ideas about nature enter into processes of tribal identity formation. Our argument is twofold. First, we argue that debates about nature are one of the primary ways tribal identities are negotiated in contemporary India. Tribal ecological claims are necessarily in relationship to the ethno-logics of the Indian state and the criteria of Scheduled Tribe; such claims are not organic expressions of primordial identities forged in social isolation but rather historically contingent and socially contextual claims that frame group identity and, in some cases, group exclusions. While tribal ecologies are not reducible to group competition for state recognition (Galanter 1984), they are necessarily expressed within such a political framework. Even without the competitive arena of state quotas, tribal ecologies would remain political in their invocation in group formation and internal differentiation.

Second, and relatedly, we argue that nature represents a terrain of politicization by which tribal communities contest state developmentalism, extractive economies, and military-paramilitary violence. Because many of India’s tribal communities live in politically sensitive areas like mining zones or militarized border landscapes, tribal claims over the alternative governance of these spaces frequently run up against powerful state and multinational actors. These contestations heighten a tribal-nature connection as claims to ecological stewardship and traditional ecological knowledge are used by tribal communities to legitimize tribal sovereignty, autonomy, and recognition. Such dynamics of tribal ecology unfold at multiple levels and with significant regional variation, structuring relations between both tribal groups and outsiders, like state bureaucrats, as well as the functioning of hierarchies internal to tribal communities themselves. For example, we see from Ladakh to Lahaul to Himachal Pradesh to Darjeeling the growing intensification of ‘Scheduled Tribe Dalit’ and inter-tribal contestation over the disenfranchising and delegitimizing legacies of casteism, classism and status hierarchies. Conversely, tribal ecologies can structure more egalitarian, and less acquisitive, relationships to nature, property regimes (Kapila 2022), and communal ownership of communal grazing lands (Axelby 2007) in comparison to mainstream caste society.

The two sides of tribal ecologies

To be clear, our concept of tribal ecology is not one solely relating to performative utterances or claim making about ecology that enable tribal groups to be constituted as subjects receiving state benefits and protections. Certainly, there is an aspect of the dynamic production of tribal identity between reservation quotas, state ethnologists and the communities themselves. But while we are neither making an argument about an “ecological primordialism” embodied in tribal knowledge and livelihood practices--as if such things persisted unchanged over time--we do insist that particular ecological relations distinguish tribal communities from other groups. This is the other side of tribal ecologies. Tribal communities, either in memory or practice, are often grounded in origin stories, lifeways, and sacralizing rituals that express relations to and knowledge about particular agro-ecologies. While these aspects of tribal identity continue to change through more extensive settled farming practices, wage work dependency, and urban migration, many tribes are still engaged in a reconstitution of community identity that foregrounds living with nature as an expression of human-ecological mutuality. This stands in contrast with orientations to nature that are extractive and exhaustive. Tribal communities can of course be destructive of ecological worlds (although often less rapidly and markedly than industrial state development). But in many parts of tribal India, the opposite is true--communal identity and belonging are produced through an engagement with nature as a vital extension of social life, observing a deference and reverence towards humanity-in-nature, rather than as separate ontological entities.

This identification with ecology has provided the groundwork for a diversity of tribal political movements throughout India. Indeed, ecology is one of the primary ways that tribal identity becomes explicitly politicized. Such movements have highlighted the long-standing symbiotic relations between tribal groups and the natural world, claiming attachments to land and territory as the basis for tribal culture and customary livelihood practices. This is even the case in contexts where tribal groups have migrated to agrarian or forest areas only in the recent past, where ecological identifications are invoked in folktales, songs, rituals, and religious practices, as well as the veneration of land associated with ancestors (Bodhi and Ziipao 2019). Such a cultural armature provides a way of framing tribal land as a source of identity formation, rather than as a commodity, or as a form of wealth that can be appropriated by the state. Many tribal movements, such as the recent pathalgadi movement in India’s central and eastern mining belt, thus invoke these attachments to land as justifications against state-induced land acquisitions, fraudulent transfers, forcible evictions, and the monetized exchange of property through mortgaging and leasing (Xaxa 2008).

Tribal ecology has thus also shaped the field of Tribal Studies in India. As one of the founding theorists of this field, Virginius Xaxa, has explained through his efforts to “decolonise” Tribal Studies, tribal relations to nature comprise an existential condition of their living. “Tribes,” Xaxa writes, “were greatly dependent on the forest for their day-to-day needs, such as food, shelter, tools, medicine and even clothing. But as long as the tribes were in control of the forest, in the sense of having unrestricted use of forest and forest produce, they had no difficulty in meeting their needs. In turn, they preserved the forest, as this was their life-support system” (Xaxa 2008: 65). This type of analysis builds on longer-standing traditions in Indian environmental studies that have foregrounded what Ramachandra Guha once called the “third world critique” of ecological conservation. This perspective moves away from viewing nature as a site of pristine wilderness, and towards a recognition of the role of Indigenous labor and livelihood practices in shaping landscapes (Guha 1989).

Such a framework is often used when discussing tribal practices of jhum or shifting cultivation, which depends on cycles of slash-and-burn dry-millet agriculture that, in ideal conditions, allows for the regeneration of soil fertility. U.A. Shimray has shown, for instance, how northeastern tribal communities practicing the jhum cycle, “observe the tree trunk and branches that indicate soil fertility. If the bark of the tree trunk is mature, the soil is considered fit for cultivation” (Shimray 2012: 60). The Gaddis of Himachal Pradesh, who have rapidly transitioned to sedentary lifeways and are largely post-pastoral, still propagate ecological knowledge about shepherding, flock care and the use of animal byproducts through ritual practice and received common knowledge. Such agro-ecological knowledge can be passed on intergenerationally, creating what Tribal Studies scholars refer to as a kind of eco-systemic awareness embedded in the cultural worldviews of forest-dwelling tribal communities.

However, the existing developmental practices of the state, which depend on the appropriation of land and resources, pose a threat to this “environmentalism of the poor” (Martinez-Alier 2002). Indigenous/tribal systems of governance, tradition, and customary laws are viewed as hurdles for development. As tribal communities have mobilized for greater decentralized decision-making for determining the trajectory and outcome of developmental projects, their voices have often been superseded by policymakers and state bureaucrats. At the same time, economic pressures on tribal communities have also changed how these communities themselves view nature and development. Money and corruption, as well as more genuine aspirations to achieve the “good life” beyond traditional village settings, have shaped local collaboration with extractive projects (Ziipao 2020).

These dynamics require greater research for understanding how invocations of tribal ecology continue to undergo transformation and reconstitution. To that end, a forthcoming Special Issue in the Tribal Intellectual Collective India Journal is dedicated to these issues, bringing together tribal scholars, grassroots organizers, international NGOs and academics from various disciplines.

Stephen Christopher is a Marie Curie anthropologist at the University of Copenhagen. Matthew Shutzer is an Assistant Professor of History at Duke University. Raile Rocky Ziipao is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at IIT Bombay.

Reference list

Axelby, Richard. 2007. “‘It takes two hands to clap’: How Gaddi shepherds in the Indian Himalayas negotiate access to grazing. Journal of Agrarian Change 7(1):35-75.

Bauman, Richard and Charles L. Briggs. 2003. Voices of Modernity: Language Ideologies and the Politics of Inequality. Berkeley: UC Press.

Betancor, Orlando. 2022. “Wars over Water: Toward an Eco-Perspectivist Subaltern Ecology”. In Castro-Klarén, S. (ed) A companion to Latin American literature and culture, pp. 728-742. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Bodhi, S.R and Ziipao, R.R.. 2019. Land, Words and Resilient Culture. The Ontological Basis of Tribal Identity. Wardha: Tribal Intellectual Collective India.

Bora, P. 2010. “Between the human, the citizen and the tribal.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 12: 341-360.

Christopher, Stephen and Peter Phillimore. 2023. “Exploring Gaddi Pluralities: An Introduction and Overview.” HIMALAYA 42(2): 3–20.

Christopher, Stephen. 2022. “Exceptional Aryans: State Misrecognition of Himachali Dalits.” In Stephen Christopher and Sanghmitra S. Acharya (eds) Caste, COVID-19, and Inequalities of Care: Lessons from South Asia pp. 13-38. Springer.

Christopher, Stephen. 2020. “‘Scheduled Tribal Dalit’ and the Recognition of Tribal Casteism.” Journal of Social Inclusion Studies: The Journal of the Indian Institute of Dalit Studies 6(1):1–17.

Christopher, Stephen. 2020a. “‘Scheduled Tribal Dalit’ and the Emergence of a Contested Intersectional Identity.” Journal of Social Inclusion Studies: The Journal of the Indian Institute of Dalit Studies 6(1):1–17.

Duara, Prasenjit. 2015. The Crisis of Global Modernity: Asian Traditions and a Sustainable Future Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object New York: Columbia University Press.

Ferguson, Brian R. 1998. “Whatever Happened to the Stone Age? Steel Tools and Yanomami Historical Ecology”. In William L. Balée (ed) Advances in Historical Ecology, pp. 287-312. New York: Columbia University Press.

Galanter, Marc. 1984. Competing Equalities: Law and the Backward Classes in India. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Govindrajan, Radhika. 2018. Animal Intimacies: Interspecies Relatedness in India’s Central Himalayas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

Guha, R. 1999. Savaging the civilized: Verrier Elwin, his Tribals, and India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Guha, R. 1989. “Radical American Environmentalism and Wilderness Preservation: A Third World Critique,” Environmental Ethics 11 (1): 71 - 83.

Kapila, Kriti. 2008. “The measure of a tribe.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 14:117-34.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. 2015. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teaching of Plants. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions.

Krech, Shepard. 1999. The Ecological Indian: Myth and History. New York: W.W. Norton.

Ludden, David. “Orientalist Empiricism: Transformations of Colonial Knowledge.” In Orientalism and the Postcolonial Predicament, edited by Carol Breckenridge and Peter van der Veer, 250-78. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Mayaram, Shail. 2014. “Pastoral Predicaments: The Gujars in History.” Contributions to Indian Sociology 48(2):191-222.

Middleton, Townsend. 2016. The demands of recognition: state anthropology and ethnopolitics in Darjeeling. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Moodie, Megan. 2015. We Were Adivasis: Aspiration in an Indian Scheduled Tribe Chicago: University of Chicago.

Morgan, Lewis H. 1877. Ancient Society. New York: H. Holt.

Omvedt, Gail. 1998. “Are Adivasis Subaltern?,” Economic and Political Weekly 23 (39), September 24.

Pagden, Anthony. 1987. The Fall of Natural Man: The American Indian and the Origins of Comparative Ethnology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pandian, Anand. 2009. Crooked Stalks: Cultivating Virtue in South India. Durham: Duke University Press.

Sarkar, Sahotra. 2008. “Whose Environmentalism?”

Sharma, Mahesh. 2023. “Shepherds, Memory, and 1947: Gaddis of the Western Himalayas.” HIMALAYA 42(2): 100-118.

Singha, Radhika. 1998. A Despotism of Law: Crime and Justice in Early Colonial India. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Skaria, Ajay. Hybrid Histories: Forests, Frontiers, and Wildness in Western India. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Still, Clarinda. 2013. “‘They have it in their stomachs but they can't vomit it up’: Dalits, reservations, and ‘caste feeling’ in rural Andhra Pradesh.” Focaal 65(12):68-79.

Xaxa, Abhay and Ganesh N. Devy (eds.). 2021. Being Adivasi: Existence, Entitlements, Exclusion. Delhi: Vintage Books.

Ziipao, Rocky Raile. 2021. “Politicising Roads in Manipur: Spatial and Temporal Relations of Infrastructure.” Economic & Political Weekly 56(4): 38-42.