Trans-Himalayas are not Wastelands

Authors

Charu Sharma, Munib Khanyari and Ajay Bijoor

Charu Sharma: Charu Sharma works as a research assistant with the High Altitudes Program at Nature Conservation Foundation. Her interests revolve around ungulate ecology and research-based conservation. Currently she is working on monitoring of snow leopard populations across large spatial scales.

Munib Khanyari: Munib Khanyari is an interdisciplinary researcher working at the interface of pastoral livelihoods and wildlife conservation. His work also focuses on more participatory and inclusive forms of co-enquiry with local communities to have meaningful co-designed conservation interventions that are contextually appropriate.

Ajay Bijoor: Ajay Bijoor works with Nature Conservation Foundation’s High-Altitude Programme and engages closely with local communities and government agencies to plan and implement conservation action in the high altitudes of Ladakh and Himachal Pradesh. He loves to explore and understand social-ecological interactions between people and nature. Ajay and his team at NCF focus on implementing community-led conservation efforts across some snow leopard landscapes in India.

Rangelands are multifunctional areas that include grasslands, pasturelands, shrublands, savannas and marshes utilized by both livestock and wildlife. Although rangelands represent about 54% of the global land cover and deliver numerous ecosystem services, they are often considered barren areas with very low productivity by the government.

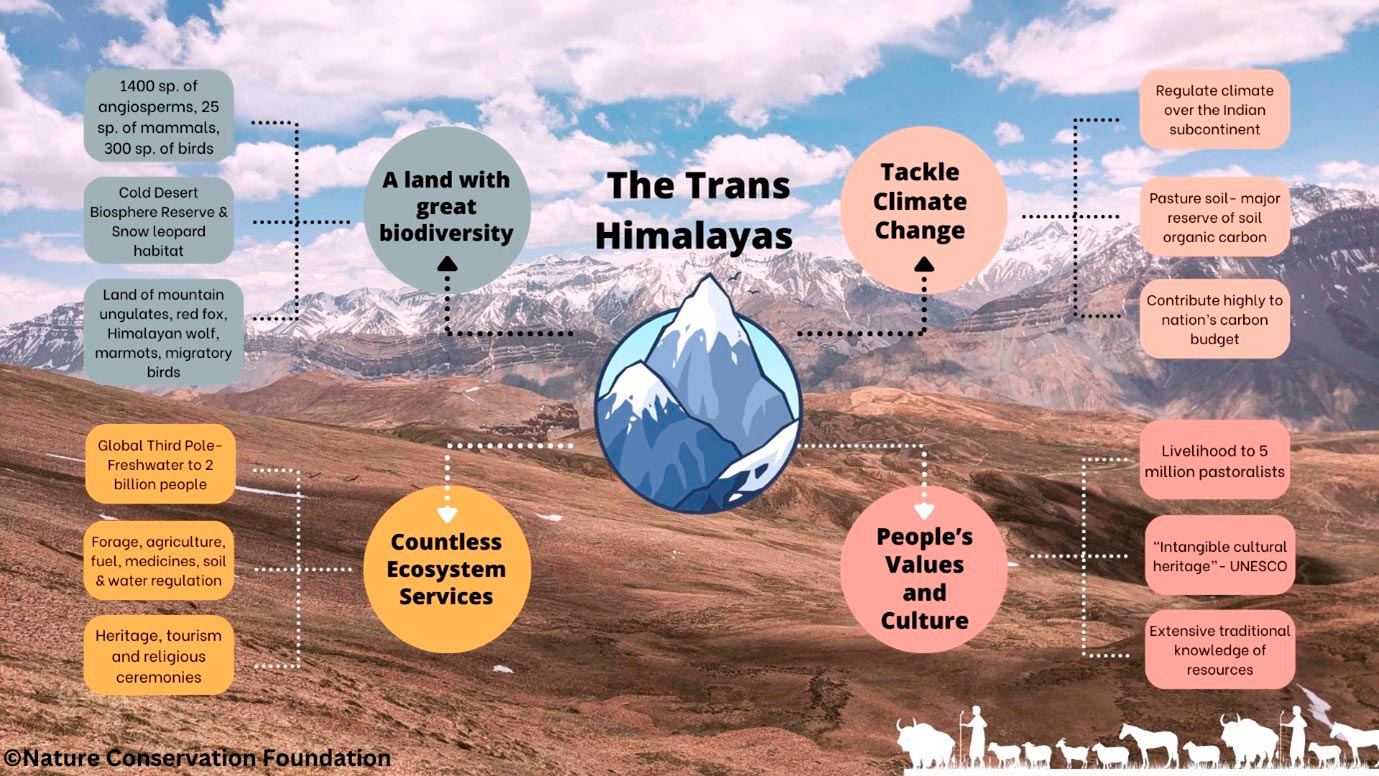

This notion is strongly felt in high elevation, low productivity rangelands of the Himalayas – i.e. regions connected to the Tibetan Plateau. Through this article, we aim to emphasize the importance of these trans-Himalayan rangelands, representing a grazing ecosystem that has supported the indigenous pastoral communities and unique wildlife for millennia. This ‘Third Pole’ and the ‘Asian Water Tower’ supports about 1.3 billion people across the continent. Being the highest grazing lands in the world, the trans-Himalaya are unique in their culture, ecosystem diversity, traditional knowledge and historical experience of the communities co-existing with nature. They are susceptible to climate change and severely under threat. We must acknowledge these global resources and seek to conserve and restore them appropriately.

Context

The High Altitudes Program of Nature Conservation Foundation & the Snow Leopard Trust have been working in the trans-Himalayan region for almost two decades now, carrying out research in the snow leopard landscape and devising measures to aid conservation with the local stakeholders. Our work spans across three states and union territories – Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and Ladakh. We study the distribution and population densities of large carnivores such as the snow leopard and its prey, the relationship and interactions of wildlife with the communities. Visiting this region and working in the vast stretches of these majestic mountains would make you realize that even in a terrain so harsh and remote, this land flourishes with life. A walk into the pastures here, and sighting a herd of ibex gives immense joy in observing them. After a difficult climb uphill when you reach the top, panting and trying to catch a breath, you get rewarded with the most incredible of views. When you notice the intricate relationship between the people, their resilience and this land, undermining the values associated is truly amiss.

Kibber, a picturesque hamlet in Spiti Valley. Picture credits: Charu Sharma

Across the world, two-thirds of the terrestrial habitats consist of non-forest biomes and open natural ecosystems (ONEs) (1). Globally, ONEs are highly threatened, as they continue to undergo sustained and rapid change due to anthropogenic pressure (2,3). Even though they occupy half of the world’s land mass, they do not receive adequate attention in today’s world of rapid development and growing economies (4). A part of the problem in conserving ONEs lies in the ambiguity in understanding what constitutes such ecosystems. While forested habitats are relatively easier to define, ONEs do not constitute a single habitat type; they can range from sandy deserts, rocky outcrops, and rubble fields to open grasslands with shrubs and scattered trees in tropical savannas (5,6). In several countries, especially where significant tracts of land are managed by foresters, ONEs, especially in semi-arid regions, have historically been regarded as degraded habitats or wastelands-due to the ‘Lockian concept’ from the colonial era- with a consequent push to increase their ‘productivity’, or to ‘develop’ them (7–9). For example, in India, large tracts of ONEs are officially categorized as waste-lands, out of which about 70% overlap with ONEs (8,10–12). Current vegetation and biogeographic classifications of India do not recognize ONEs and continue to use a ‘forest’ classification (13,14) , even for habitats that fall within the bioclimatic envelope of tropical savanna ecosystems (15). Much of this misclassification by John Locke can be attributed to the historical colonial focus on forestry and economic productivity.

While now there is a pushback against the whole “wasteland” concept in the country by ecologists and practitioners working in similar ecosystems advocating the need to rethink this idea, often the trans-Himalayan regions get missed from these discussions (12,16). A “Wasteland Atlas of India” was prepared by the Department of Land Resources showcasing the distribution of various kinds of “waste” lands across states to further inform planning and development for each state (10). Ecologically sensitive areas such as the lands with open scrub (underutilised forests), snow-covered/glacial areas, barren rocky outcrops and degraded pastures/grazing lands, all have been marked as wastelands in the atlas (10,17). Moreover, extensive tree plantation drives and greening campaigns for these ecosystems can prove to be detrimental, despite the noble intentions behind them (18–22). The Wasteland notions of these lands dilute the Environmental Impact Assessment process which renders these areas vulnerable to “development” projects, especially green energy projects in pursuit of India’s commitment to meet climate targets. This fails to look at the effect of everlasting impact, intensive resource consumption and jeopardizing people’s livelihoods.

Therefore, with this piece, we want to challenge the prevailing narrative and champion the fact that the Indian trans-Himalayas are not at all wastelands but immeasurably more than that by looking at various aspects of these unique landscapes.

What makes the Indian Trans-Himalayas (ITH) different?

The Indian Trans-Himalayas, situated beyond the Greater Himalayas is a rain-shadow zone connected to the Eurasian steppes and the history of pastoralism here dates back to at least 3 millennia (23,24). They are commonly called rangelands as they are widely for herding livestock. While these areas host unparallel diversity and deliver numerous ecosystem services- forage for livestock and wildlife, water regulation and storage, carbon sequestration- half of them are degraded (4,25,26). The high-elevation rangelands of the trans-Himalaya (up to 5100 m above MSL) spread over 2.6 million km2 represent a grazing ecosystem providing livelihoods to 5 million pastoralists (23,25). Characteristic features of this region include extreme climatic conditions, rugged terrain, high diurnal variation in temperature, very little rainfall (<50 mm), and freezing winters with snow (24,27).

A land booming with diversity

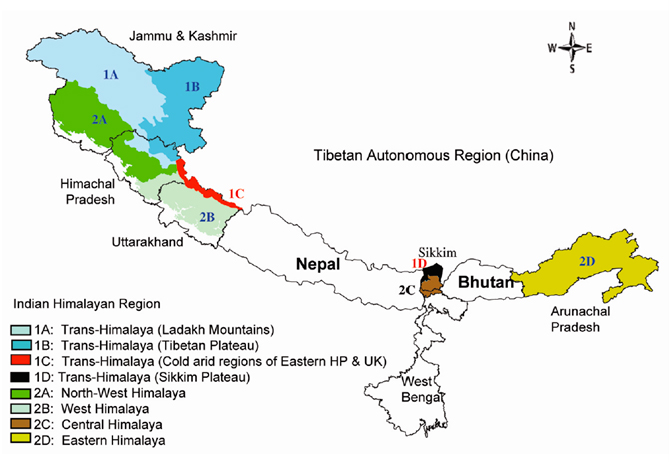

Within the graminoid-dominating habitats, the trans-Himalayas are said to be the least productive with sparse vegetation (23,24). Despite this, the fragile ecosystem here hosts amazingly rich biodiversity. The Hindu Kush Himalayan region have 4 out of the 36 global biodiversity hotspots (28,29). The biogeographic provinces covered are- the Ladakh mountains and valleys of Kargil, Leh, Zanskar and Lahaul-Spiti area, the Tibetan plateau covering Changthang, Spiti and small pockets of Uttarakhand, and the cold deserts of North Sikkim (30,31).

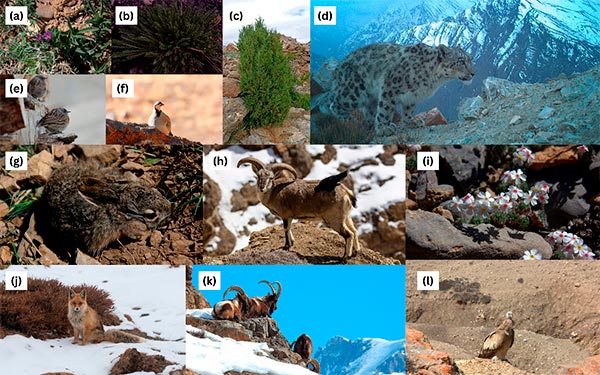

The ITH is home to more than 1400 species of angiosperms, 25 species of mammals, 36 species of insects and more than 300 species of birds (23,30). Grasses and sedges like Stipa (vernacular name-Simo), Carex, shrubs such as Caragana (Thama), Indian milkvetch, rock jasmine, Artemisia, Eurotia (Burche), Ephedra (Che), and trees of juniper, willow, birch (Thappa) mixed communities (24,27,33,34) found here have extensive values. Ungulates such as the Asiatic ibex, blue sheep, Tibetan argali, Tibetan gazelle, Ladakh urial, alongside other animals like the marmots, red fox, stone marten, pika, Pallas’s cat are found here. The majority of the snow leopard habitat comes under the trans-Himalayas (35). To preserve the distinctive cold desert ecosystem of the ITH, part of this landscape has been declared as the Cold Desert Biosphere Reserve (36). These mountains also harbour numerous High Altitude Wetlands which are extremely crucial for various migratory birds, people and wildlife (30). They act as breeding sites for avifauna such as the black necked crane, bar headed goose, Tibetan snowcock, golden eagle, and Tibetan sandgrouse, to name a few (23).

A region offering countless ecosystem services

The trans-Himalayas and adjacent mountains are better known as the ‘Third Pole’ and the ‘Asian Water Tower’ (37,38) for being the largest freshwater reserve after the poles, supplying 50% of the country’s total utilizable surface water resources, and freshwater to about 2 billion people across the continent (28,39). These snow-covered lands during winters are important pastures used by the locals to graze their livestock- sheep, goats, yaks, horses (40,41). The region provides various provisioning services like animal dung for fuel, fodder, edible plants, wood, cultivated crops, regulatory services of climate and soil regulation etc (42). More than 300 species of plants are used for medicinal purposes (Sowa Rigpa- Tibetan medicine system) (30,43). In monetary terms, the value of provisioning services provided by these mountains was 3.8 times more than the average household income, which surpass values derived from high productivity habitats like forests and mangroves (42).

Benefits in fighting climate change

The trans-Himalayas are extremely sensitive to rising global temperatures as they regulate the climate over the entire northern region of the Indian subcontinent (44,45). Due to their special orography, they influence the south-Asian monsoon wind circulation and also prevent the dry cold winds from Central Asia to entering the subcontinent (46). Grassland ecosystem and soil organic carbon (SOC) play an important role in carbon storage and climate change adaptation (47–49). The traditional and sustainable grazing system in the trans-Himalayas has helped maintain high plant diversity and productivity where livestock aid in seed dispersal (50). This increased diversity provides better resource utilization and supports carbon capture (28). Grazing also modifies the soil microbiome towards fungi which have higher net carbon storage (51).

In addition, by slowing down the pace of decomposition, the low soil temperature in the western Himalaya enables the soil to store more organic carbon (52). The wetlands, permafrost soils and peat collectively contribute highly to the nation’s carbon budget and are vital in the global carbon cycle and potential feedback to climate change (52).

Pastures like these are important for soil organic carbon, supporting people, livestock and wildlife; Spiti Valley, Himachal Pradesh. Picture credits: Charu Sharma

People’s rights and cultural significance

The life of the people residing here is intertwined with this ecosystem. The region carries vibrant and unique histories of various communities and their socio-cultural practices (53). Herders from various communities reside here; such as the Brokpa and Changpa in Ladakh, Gujjars & Bakarwals from Jammu & Kashmir, Gujjars, Gaddis, Kinnauras, Lahaula and Spitian from Himachal Pradesh & Uttarakhand, and the Dokpa, Gurung, Bhutia in Sikkim (54,55). They have extensive traditional knowledge on the everyday and seasonal factors determining livestock grazing, the judicious spatial-temporal use of pastures (sharing) and the locally prepared high-nutrient stall feeds for the lean winters (56). Despite changing shifts in the idea of ‘tradition’, certain indigenous ways of being and living such as organisation of agriculture, ritual, religion, aesthetic, art, and architecture have, to an extent, preserved their character (36). The sacred Buddhist chanting of Ladakh has been honoured by the UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage. By determining these as wastelands, we are overlooking this intricate bond between these people and their lands.

Settlements are sparse in the difficult terrain; Location: Lossar Village, Spiti Valley, Himachal Pradesh. Picture credits: Charu Sharma

Pastoralists have exhibited extraordinary resilience over generations due to their experiential patterns of migration (25). The villages are tiny, remote, and scarcely inhabited; their layout is an indicator of the severity of this landscape (36). The social systems aim to maximize production while balancing environmental risk (57). It is imperative to ensure the traditional customary rights to the usage of these resources and their grazing lands are protected and maintained (58).

A land under pressure!

Rangelands face several pressures. Climate change poses a major threat to the livelihood and food security of pastoralists due to degradation of pastures and rangeland health. Continued global warming is leading to substantial loss of glacial cover impacting stream flows, agriculture, tourism, hydropower and an increased threat of glacial lake outburst floods; all of which is risking the livelihoods of mountain communities (38).

Albeit remote these areas are affected by developmental changes occurring at the global level which in turn act on the local scale as well. Socio-economic changes, livelihood diversification, fragmentation of pastures, military expansion and free-ranging dogs are some of the factors impeding the herding practices and damaging these rangelands (40,41). A sharp increase in tourism, vehicular emissions, solid waste and activities such as off-roading in the pastures assumed ‘barren’ deteriorate the rangelands (59–61). Extreme shifts in weather patterns, erratic snowfall leads to uncertain floods, landslides and droughts (62,63). Increase in urbanization coupled with climate insecurity is causing outmigration of people to urban settlements- threatening their livelihoods and survival (40,64). On top of that, these rangelands are being perceived as ideal locations for expansive solar plants, with no evaluation of the local costs to the environment, resources and the people (65). Renewable energy is required to curb the increasing energy demands of a developing nation, but the long-term impacts and social and ecological costs need to be assessed holistically.

What can be done?

Different from the rest of the world, the trans-Himalaya have unique physical, biological, hydrological, and anthropological settings defining its ecological and conservational significance (24,30). We think it is important to re-think the narrative of trans-Himalayas as “wastelands” because it leads to irresponsible use of these fragile ecosystems. Despite the alarming threats and global concern, these regions have not received adequate attention. The United Nations General Assembly has declared 2026 as the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists (IYRP 2026) to work towards improving rangeland health and lives of the herders (4). The UN decade on Ecosystem Restoration further emphasizes the need to ecologically restore these grasslands and rangelands, as equally as any other ecosystem. Studies suggest that with effective restoration, the carbon capturing potential of grasslands managed by pastoralists increases (49).

Nature and culture have thrived in this region for generations. A paradigm change in management is required to stop degradation of these rangelands, from the baselines at local levels to the global scale (4). We need to move beyond the historical anomaly to recognize and acknowledge the value of ONEs. One of the ways to do so is through education and empowerment of the local people as well as those who visit these areas. Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) can be explored as a strategy to preserve these lands with fair and equitable participatory process bringing about positive socio-economic outcomes (25,66). Conservation of this region also calls for co-management of rangeland resources with collaborations between all parties, healthy dialogue and joint interventions to address the issues (67). It is useful to recognize the local governance structures to support the creation of better, inclusive institutions and policies with participation of the communities and institutionalizing their resources (68). Conflict mitigation from loss due to wildlife can aid in positive promotion of coexistence between people and wildlife (69). Management of livestock stocking rates with sustainable utilization of pastures are some more aspects to be mindful of (70,71).

Finally, and most importantly, like the Amazon is the lungs of the Earth, we need to realize that the ITH is a national and international asset with spectacular landscapes and values for both people and nature.

- Dinerstein E, Olson D, Joshi A, Vynne C, Burgess ND, Wikramanayake E, et al. An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm. BioScience. 2017 Jun;67(6):534–45.

- White RP, Murray S, Rohweder M, Prince SD, Thompson KM. Grassland ecosystems [Internet]. World Resources Institute Washington, DC, USA; 2000 [cited 2024 Aug 4]. Available from: https://www.365lewuyou.com/files/d8/s3fs-public/pdf/page_grasslands.pdf

- Veldman JW, Buisson E, Durigan G, Fernandes GW, Le Stradic S, Mahy G, et al. Toward an old-growth concept for grasslands, savannas, and woodlands. Front Ecol Environ. 2015;13(3):154–62.

- UNCCD. ‘Silent demise’ of vast rangelands threatens climate, food, wellbeing of billions [Internet]. United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. 21 May 24 [cited 2024 Aug 3]. Available from: https://www.unccd.int/news-stories/press-releases/silent-demise-vast-rangelands-threatens-climate-food-wellbeing-billions

- Ratnam J, Bond WJ, Fensham RJ, Hoffmann WA, Archibald S, Lehmann CER, et al. When is a ‘forest’ a savanna, and why does it matter? Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2011;20(5):653–60.

- Wrobel ML, Redford KH. Introduction: A Review of Rangeland Conservation Issues in an Uncertain Future. In: Du Toit JT, Kock R, Deutsch JC, editors. Wild Rangelands: Conserving Wildlife While Maintaining Livestock in Semi-Arid Ecosystems [Internet]. 1st ed. Wiley; 2010 [cited 2024 Aug 3]. p. 1–12. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781444317091.ch1

- Baka J. Making Space for Energy: Wasteland Development, Enclosures, and Energy Dispossessions. Antipode. 2017;49(4):977–96.

- Vanak AT. Wastelands of the mind: the identity crisis of India’s savanna grasslands. Plenary Lect 3. 2019;33–4.

- Whitehead J. John Locke and the Governance of India’s Landscape: The Category of Wasteland in Colonial Revenue and Forest Legislation. Econ Polit Wkly. 2010;45(50):83–93.

- Government of India. Wastelands Atlas of India [Internet]. Department of Land Resources, Ministry of Rural Development; 2019 [cited 2024 Apr 8]. Available from: https://dolr.gov.in/wasteland-atlas-of-india-2019/

- Vanak AT, Hiremath AJ, Krishnan S, Ganesh T, Rai ND. Filling in the (forest) blanks: the past, present and future of India’s savanna grasslands. Transcending Boundaries Reflecting Twenty Years Action Res ATREE Ashoka Trust Res Ecol Environ Karnataka 189pp. 2017;88–93.

- Madhusudan MD, Vanak AT. Mapping the distribution and extent of India’s semi-arid open natural ecosystems. J Biogeogr. 2023;50(8):1377–87.

- Champion HG, Seth SK. A Revised Survey of the Forest Types of India, 1968 [Internet]. New Delhi: Government of India Publications; 1968. 405 p. Available from: https://books.google.co.in/books/about/A_Revised_Survey_of_the_Forest_Types_of.html?id=hIjwAAAAMAAJ

- Puri GS, Meher-Homji VM, Gupta RK, Puri S. Forest ecology. Volume I. Phytogeography and forest conservation. [Internet]. New Delhi, India: Oxford & IBH Publishing Co.; 1983 [cited 2024 Aug 9]. xxii + 549. Available from: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/19840694794

- Ratnam J, Sheth C, Sankaran M. African and Asian Savannas. In: Savanna Woody Plants and Large Herbivores [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2019 [cited 2024 Aug 3]. p. 25–49. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781119081111.ch2

- Watve A, Athreya V, Majgaonkar I. The Need to Overhaul Wasteland Classification Systems in India. Econ Polit Wkly. 2021 Oct 2;56(40):36–40.

- Varma K. Wastelands of India [Internet]. Peepli. 2015 [cited 2024 Aug 4]. Available from: https://www.peepli.org/stories/wastelands-of-india/

- Administration of Union Territory of Ladakh. The Mega Plantation Drive organised by Live to Love, Young Drukpa Association, Trees for Life in association with LAHDC Leh, commenced yesterday at Liktsey village in Rong Churgyud. | The Administration of Union Territory of Ladakh | India [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 4]. Available from: https://ladakh.gov.in/the-mega-plantation-drive-organised-by-live-to-love-young-drukpa-association-trees-for-life-in-association-with-lahdc-leh-commenced-yesterday-at-liktsey-village-in-rong-churgyud/

- Tribune Web Desk. One lakh saplings to be planted in Ladakh region on May 17. The Tribune [Internet]. 2023 May 7 [cited 2024 Aug 4]; Available from: https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/j-k/one-lakh-saplings-to-be-planted-in-ladakh-region-on-may-17-505708/

- Vanak A, Misher C. Why massive tree plantation drives are a disaster for desert ecosystems [Internet]. Scroll.in. 2022 [cited 2024 Aug 4]. Available from: https://scroll.in/article/1026330/why-massive-tree-plantation-drives-are-a-disaster-for-desert-ecosystems

- Veldman JW, Overbeck GE, Negreiros D, Mahy G, Le Stradic S, Fernandes GW, et al. Where Tree Planting and Forest Expansion are Bad for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. BioScience. 2015 Oct 1;65(10):1011–8.

- Fleischman F, Basant S, Chhatre A, Coleman EA, Fischer HW, Gupta D, et al. Pitfalls of Tree Planting Show Why We Need People-Centered Natural Climate Solutions. BioScience. 2020 Nov 17;70(11):947–50.

- Mishra C, Bagchi S, Namgail T, Bhatnagar YV. Multiple use of Trans-Himalayan Rangelands: Reconciling Human Livelihoods with Wildlife Conservation. In: Wild Rangelands [Internet]. Wiley; 2010 [cited 2024 Aug 4]. p. 291–311. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781444317091.ch11

- Kumar A, Adhikari BS, Rawat GS. Rangeland vegetation of the Indian Trans-Himalaya: An ecological review. Ecol Manag Grassl Habitats India. 2015;28–41.

- Joshi L, Shrestha RM, Jasra AW, Joshi S, Gilani H, Ismail M. Rangeland ecosystem services in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region. High-Alt Rangel Their Interfaces Hindu Kush Himalayas. 2013 Nov 20;157–89.

- Miller DJ. Pastoral development in the HKH: Organising rangeland and livestock research for the twenty-first century. In: Proceedings of the seminar on farming systems research in the context of food security, held at Dera Ghazi Khan Pakistan. 1996. p. 4–6.

- Sharma L, Samant SS. Prioritization of habitats and communities for conservation in Cold Desert Biosphere Reserve, Trans Himalaya, India. Ecol Res. 2019;34(4):509–23.

- Kattel GR. Climate warming in the Himalayas threatens biodiversity, ecosystem functioning and ecosystem services in the 21st century: is there a better solution? Biodivers Conserv. 2022 Jul 1;31(8):2017–44.

- Kotru RK, Shakya B, Joshi S, Gurung J, Ali G, Amatya S, et al. Biodiversity conservation and management in the Hindu Kush Himalayan Region: are transboundary landscapes a promising solution? Mt Res Dev. 2020;40(2):A15.

- Rawal RS, Bhatt ID, Sekar KC, Nandi SK. The Himalayan Biodiversity: Richness, Representativeness, Uniqueness and Life-support Values [Internet]. Uttarakhand, India: G B Pant Institute of Himalayan Environment and Development (GBPIHED); 2013 [cited 2024 Aug 2]. 84 p. Available from: https://gbpihed.gov.in/PDF/Publication/Himalayan_Biodiversity_2013_book.pdf

- Rodgers WA, Panwar SH, Mathur VB. Wildlife Protected Area Network in India: A Review (Executive Summary). Wildl Inst India Dehradun. 2000;

- Kumar A, Adhikari BS, Rawat GS. A hierarchy of landscape-habitat-plant physiognomic classes in the Indian Trans-Himalaya. Trees For People. 2022 Mar 1;7:100172.

- Joshi PK, Rawat GS, Padilya H, Roy PS. Biodiversity Characterization in Nubra Valley, Ladakh with Special Reference to Plant Resource Conservation and Bioprospecting. Biodivers Conserv. 2006 Dec 1;15(13):4253–70.

- Rawat GS. Alpine vegetation of the western Himalaya: species diversity, community structure, dynamics and aspects of conservation [Internet] [PhD Thesis]. Kumaun University, Nainital; 2007 [cited 2024 Aug 4]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Gopal-Rawat-4/publication/268606959_ALPINE_VEGETATION_OF_THE_WESTERN_HIMALAYA_SPECIES_DIVERSITY_COMMUNITY_STRUCTURE_DYNAMICS_AND_ASPECTS_OF_CONSERVATION_Thesis_submitted_For_the_award_of_DOCTOR_OF_SCIENCE_In_Botany/links/5471a22c0cf24af340c3c063/ALPINE-VEGETATION-OF-THE-WESTERN-HIMALAYA-SPECIES-DIVERSITY-COMMUNITY-STRUCTURE-DYNAMICS-AND-ASPECTS-OF-CONSERVATION-Thesis-submitted-For-the-award-of-DOCTOR-OF-SCIENCE-In-Botany.pdf

- Bhatnagar YV, Mathur VB, Sathyakumar S, Pal R, Ghoshal A, Sharma RK, et al. Chapter 41 - Securing India’s snow leopards: Status, threats, and conservation. In: Mallon D, McCarthy T, editors. Snow Leopards (Second Edition) [Internet]. Academic Press; 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 4]. p. 513–29. (Biodiversity of World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780323857758000030

- Delegation of India. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2015 [cited 2024 Aug 2]. Cold Desert Cultural Landscape of India. Available from: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6055/; Christopher, Stephen. 2023. “Priestly Purity: Status Competition in the Tribal Margins.” HIMALAYA 42(2): 51–69.; Christopher, Stephen, Matthew Shutzer, Raile Rocky Ziipao. 2023. “An Introduction to Tribal Ecologies in Modern India.” Journal of the Tribal Intellectual Collective India 7(1): 1–18.

- Yao T, Thompson LG, Mosbrugger V, Zhang F, Ma Y, Luo T, et al. Third Pole Environment (TPE). Environ Dev. 2012 Jul 1;3:52–64.

- Majeed U, Rashid I, Sattar A, Allen S, Stoffel M, Nüsser M, et al. Recession of Gya Glacier and the 2014 glacial lake outburst flood in the Trans-Himalayan region of Ladakh, India. Sci Total Environ. 2021 Feb 20;756:144008.

- Scott CA, Zhang F, Mukherji A, Immerzeel W, Mustafa D, Bharati L. Water in the Hindu Kush Himalaya. In: Wester P, Mishra A, Mukherji A, Shrestha AB, editors. The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: Mountains, Climate Change, Sustainability and People [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019 [cited 2024 Aug 5]. p. 257–99. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92288-1_8

- Ladon P, Nüsser M, Garkoti SC. Mountain agropastoralism: traditional practices, institutions and pressures in the Indian Trans-Himalaya of Ladakh. Pastoralism. 2023 Nov 20;13(1):30.

- Luxom NM, Singh R, Theengh L, Shrestha P, Sharma RK. Pastoral practices, pressures, and human-wildlife relations in high altitude rangelands of eastern Himalaya: A case study of the Dokpa pastoralists of North Sikkim. Pastoralism. 2022 Sep 2;12(1):37.

- Murali R, Redpath S, Mishra C. The value of ecosystem services in the high altitude Spiti Valley, Indian Trans-Himalaya. Ecosyst Serv. 2017 Dec;28:115–23.

- Gurmet P. “Sowa - Rigpa” : Himalayan art of healing. Indian J Tradit Knowl CSIR. 2004 Apr;3(2):212–8.

- Shekhar MS, Chand H, Kumar S, Srinivasan K, Ganju A. Climate-change studies in the western Himalaya. Ann Glaciol. 2010 Jan;51(54):105–12.

- Meng Y, Duan K, Shi P, Shang W, Li S, Cheng Y, et al. Sensitive temperature changes on the Tibetan Plateau in response to global warming. Atmospheric Res. 2023 Oct 1;294:106948.

- Sabin TP, Krishnan R, Vellore R, Priya P, Borgaonkar HP, Singh BB, et al. Climate Change Over the Himalayas. In: Krishnan R, Sanjay J, Gnanaseelan C, Mujumdar M, Kulkarni A, Chakraborty S, editors. Assessment of Climate Change over the Indian Region: A Report of the Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES), Government of India [Internet]. Singapore: Springer; 2020 [cited 2024 Jul 31]. p. 207–22. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4327-2_11

- Conant RT, Paustian K, Elliott ET. Grassland Management and Conversion into Grassland: Effects on Soil Carbon. Ecol Appl. 2001;11(2):343–55.

- Jackson LE, Potthoff M, Steenwerth KL, O’Geen AT, Stromberg MR, Scow KM. Chapter 9 Soil Biology and Carbon Sequestration in Grasslands. In: Stromberg M, Corbin J, D’Antonio C, editors. California Grasslands [Internet]. University of California Press; 2007 [cited 2024 Aug 5]. p. 107–18. Available from: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1525/9780520933972-015/html

- Bhan M, Misher C, Hiremath AJ, Vanak AT. Land management controls on soil carbon fluxes in Asia’s largest tropical grassland [Internet]. EarthArXiv; 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 1]. Available from: https://eartharxiv.org/repository/view/7141/

- Ingty T. Pastoralism in the highest peaks: Role of the traditional grazing systems in maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem function in the alpine Himalaya. PLOS ONE. 2021 Jan 7;16(1):e0245221.

- Bagchi S, Roy S, Maitra A, Sran RS. Herbivores suppress soil microbes to influence carbon sequestration in the grazing ecosystem of the Trans-Himalaya. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2017 Feb 15;239:199–206.

- Rawat D, Sati SP, Khanduri VP, Riyal M, Mishra G. Carbon Sequestration Potential of Different Land Use Sectors of Western Himalaya. In: Pant D, Kumar Nadda A, Pant KK, Agarwal AK, editors. Advances in Carbon Capture and Utilization [Internet]. Singapore: Springer; 2021 [cited 2024 Aug 3]. p. 273–94. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-0638-0_12

- Banerji G, Fareedi M. Protection of cultural diversity in the Himalayas. In: A background paper for a workshop on addressing regional disparities: Inclusive & culturally attuned development for the Himalayas [Internet]. New Delhi, India; 2009. Available from: https://www.pragya.org/doc/Cultural-diversity.pdf

- Singh R, Kerven C. Pastoralism in South Asia: Contemporary stresses and adaptations of Himalayan pastoralists. Pastoralism. 2023 Aug 18;13(1):21.

- Christopher S, Phillimore P. Exploring Gaddi Pluralities: An Introduction and Overview. HIMALAYA - J Assoc Nepal Himal Stud. 2023 Aug 23;42(2):3–20.

- Singh R, Sharma RK, Babu S, Bhatnagar YV. Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Contemporary Changes in the Agro-pastoral System of Upper Spiti Landscape, Indian Trans-Himalayas. Pastoralism. 2020 Jul 17;10(1):15.

- Mishra C, Prins HHT, Van Wieren SE. Diversity, Risk Mediation, and Change in a Trans-Himalayan Agropastoral System. Hum Ecol. 2003 Dec 1;31(4):595–609.

- Rathore V. New awakenings in the trans-Himalaya [Internet]. Down To Earth. 2018 [cited 2024 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/forests/new-awakenings-in-the-trans-himalaya-62303

- Tripathi S. We need to protect Ladakh. And time is running out. [Internet]. India Today. 2022 [cited 2024 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.indiatoday.in/environment/story/climate-change-global-warming-ladakh-environment-grassland-wildlife-ut-geology-2291457-2022-10-31

- Kothari A, Deachen K. Can Ladakh Embrace Tourism While Protecting Its Fragile Ecosystem? [Internet]. Outlook Traveller. 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 2]. Available from: https://www.outlooktraveller.com/destinations/india/can-ladakh-embrace-tourism-while-protecting-its-fragile-ecosystem

- Namgail T. Ladakh | All is not well at Changthang Wildlife Sanctuary. The Hindu [Internet]. 2024 Jul 12 [cited 2024 Aug 5]; Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/energy-and-environment/ladakh-changthang-wildlife-sanctuary-conservation-tsewang-namgail-snow-leopard-tourism/article68384267.ece

- Kumar RS, Yangchan P. Climate Change Impact on Leh, A Glacier – Reliant Town: Adapative Responses, Impacts, and Solutions. Geogr Anal. 2021 May 22;10(1):17–27.

- Pandey K, Azmat H. Mongabay-India. 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 1]. Rapid urbanisation and climate change threaten groundwater resources in Ladakh, says study. Available from: https://india.mongabay.com/2024/07/rapid-urbanisation-and-climate-change-threaten-groundwater-resources-in-ladakh-says-study/

- Khan M. Aljazeera. 2023 [cited 2024 Jan 9]. Photos: Ladakh herders struggle on the frontier of climate crisis. Available from: https://www.aljazeera.com/gallery/2023/1/10/photos-ladakh-herders-struggle-on-the-frontier-of-climate-crisis

- Kapoor M. Mega Solar Park Could Put Spiti on Thin Ice in India’s Himachal Pradesh | Earth Journalism Network [Internet]. Earth Journalism Network. 2022 [cited 2024 Aug 2]. Available from: https://earthjournalism.net/stories/mega-solar-park-could-put-spiti-on-thin-ice-in-indias-himachal-pradesh

- Gaworecki M. Mongabay Environmental News. 2017 [cited 2024 Sep 1]. Cash for conservation: Do payments for ecosystem services work? Available from: https://news.mongabay.com/2017/10/cash-for-conservation-do-payments-for-ecosystem-services-work/

- Zhaoli Y. Co-management of Rangeland Resources in HinduKush Himalayan Region: Involving farmers in the Policy Process. Int Centrefor Integr Mt Dev [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2024 Apr 8]; Available from: https://www.icimod.org/resources/688

- Murali R, Bijoor A, Thinley T, Gurmet K, Chunit K, Tobge R, et al. Indigenous governance structures for maintaining an ecosystem service in an agro-pastoral community in the Indian Trans Himalaya. Ecosyst People. 2022 Dec 31;18(1):303–14.

- Jackson R, Wangchuk R, Hillard D. Grass roots measures to protect the endangered snow leopard from herder retribution: lessons learned from predator-proofing corrals in Ladakh. Int Snow Leopard Trust Seattle Wash USA. 2002 May;104–17.

- Mishra C, Prins HHT, Wieren SE van. Overstocking in the trans-Himalayan rangelands of India. Environ Conserv. 2001 Sep;28(3):279–83.

- Sharma RK, Bhatnagar YV, Mishra C. Does livestock benefit or harm snow leopards? Biol Conserv. 2015 Oct 1;190:8–13.